VENT: Dew the Right Thing

As roofers are well aware, leaks don’t always come from the top. Rather than digging up a valley or caulking a scupper for the third time, callbacks and premature failure can be reduced by addressing ventilation concerns before installation. Some manufacturers are also promoting the use of ventilation products as profit centers even when roofing replacement doesn’t enter the picture; others sell products to general, roofing and insulation contractors.

The science behind roof ventilation has developed some innovative approaches and national codes reflect a near universal recognition of the problem, but there are so many variables for each building that some concepts are still emerging. The range of solutions offered today means that roofing and insulation contractors must stay on top of the physical properties that may not directly involve their trade, but certainly will when leaks appear in the ceiling.

Get Out of the House

Before the days of R-values and vapor retarders, buildings were drafty enough to release much of the interior’s conditions, whether it was heat or moisture. Even before the energy crisis of the 1970s changed the landscape dramatically, builders and designers were aware of how condensation forms in buildings. Cupolas and roof “lanterns” were employed to draft the structures; empty cavity walls allowed moisture to dissipate and radiators were usually placed in front of windows to keep condensation from forming there.As homes became more energy efficient, some in the northern climates developed ice dams and experienced chronic leaks and damage to the roof assembly and even decking. Today’s modern homeowners, in a never ending quest to understand their houses better, are more savvy about concepts like ventilation and dew points. If class action suits are used as a barometer, mold has become a major concern for homeowners. Still, roofing contractors play a pivotal role in providing a comprehensive approach to the unique demands of their structures.

“They have to educate the homeowners,” says Steve Feldman, marketing manager for ADO Products Inc. of Rogers, Minn. “Attic ventilation is something relatively new. People used to say just increase the R-value.”

The problem for many homes is that the amount of moisture generated by occupants can have an accumulative effect. According to government research, a family of four can generate from 1 1/2 to 2 gallons of moisture each day that migrates to areas where it’s cooler and drier. When the Sistine Chapel in Rome was restored several years ago and the building enclosed for the first time, engineers anticipated a moisture problem from the thousands of visitors. Climate control devices were designed to handle the large volumes of, well, sweat, which could collect and damage Michelangelo’s masterpiece.

In most cases it collects in the attic where it waits as ice or liquid before gravity and summer heat return the favor and the water comes back downward. The damage can go unnoticed for some time, complicating the search for the true culprit. “We get a lot of calls from people adding ventilation to their existing homes,” says Feldman, whose company has been making roof vents since 1988. “We also get calls from people who have problems.”

These represent consumers that are already sold on the concept of ventilation. From there it’s a horse race where the winner is the one with the most expertise and best customer service; value is a distant concern for someone with a recurring problem that has endured several fixes. ADO Products makes a variety of solutions for both roofing and insulation contractors on new and retrofit projects.

While getting moisture out is the main function of ventilation products, channeling that circulation through piles of insulation is the job of a new rigid plastic version of Pro-Vent. While new construction allows the installation of a soft foam vent that’s installed between the rafters at soffit vents — a job primarily for insulation contractors — the rigid Pro-Vent can be inserted on retrofit jobs in tight quarters by roofing contractors. To complete the picture, ADO Products even offers a Quick-Seal attic hatch that stops vapor with a foam gasket and insulated cover.

Reaching contractors with sales material is a big focus for the company, while also addressing new wrinkles in the building’s design. Wind-driven rain, gaps between the rafter/joists and insulation blocking vents used to be handled by the rather low-tech application of card board.

The company was just awarded a patent for its Wind Block, which is an L-shaped polyboard form that solves all three problems and it costs less than having crews cut cardboard to size. “It’s always been a problem area,” says Feldman. “Someone has to deal with it. We saw that there was no blockage.”

Department of Interior

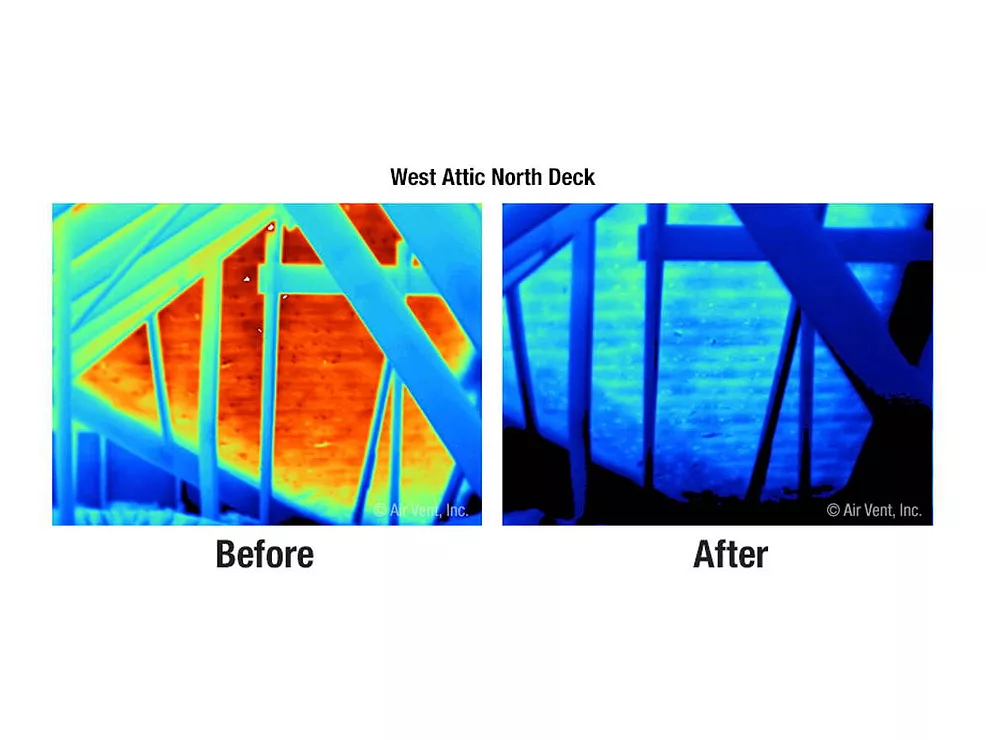

Attic ventilation used to be concentrated in the Snow Belt where roofs with a 4:12 pitch gathered snow for months and warmth from below created those lovely icicles on the overhangs. Most homeowners realize after one season that icicles are not a scenic herald of winter but a spring disaster in the making. The Internet has helped educate homeowners, but there is still a learning curve when it comes to other properties to be concerned about, like how excessive heat build up in the summer can accelerate the aging of asphalt shingles, sometimes even voiding the warranty.Shingle Vent, introduced in 1985, was among the first wave of ridge vents that used the very apex of the roof as the vent. It also blended in with the existing ridge and eliminated penetrations caused by traditional rooftop vents like turtles and turbines. Air Vent Inc., makers of Shingle Vent, went high-tech in 1991 when it introduced Shingle Vent II with external bafflers that use avionics to increase air flow. The product has undergone three refinements since then.

“When the wind hits the baffle, it jumps over the vent and creates pressure that draws air through it,” says Marianne Horvat, vice-president of marketing for Air Vent in Dallas. The even airflow created by ridge vents makes them the system of choice for contractors. “That’s why people are using more ridge vents. And it looks a lot better.”

Another reason is the building code, which measures the efficacy of vents by their net-free area. This can get confusing for homeowners and contractors since foam and mesh are necessary components for any ridge vent to block out precipitation, dust and pests. Air Vent has made an extensive effort to educate consumers with a CD-ROMs and a video that promote good roof design and the use of professional roofing contractors. While terms like “thermal buoyancy” (the rising warm air that makes static vents work) and the “Bernoulli effect” (the phenomenon of air flow that gives wings their lift) may have some scratching their heads, collateral material and multi-media presentations do a convincing job of tackling tough subjects in a world where homeowners only think about their roof when it’s leaking.

All that lift begs the question: Will high winds create too much lift and rip the device off? Horvat responds that the Shingle Vent II — which comes in three sizes — has passed Miami-Dade County’s stringent uplift requirements. Another product, FilterVent, is for high-profile roofs like shakes and tile and is available in zinc to combat mold on the exterior of the roof. Another recent development that further increases airflow is a solar-powered roof vent introduced by the company in 2001. Available through both Lowe’s and traditional roofing distributors, the device — which draws up to 800 cubic feet of air per minute — already displayed some unexpected selling patterns by selling well in Michigan but not in Florida.

“It’s just not selling in Florida like other areas of the country,” says Horvat. “California is huge. The utilities in California have been very good about pushing these things.”

No Sweat

It can be an uphill battle when trying to rise above the pack with a product that barely registers on the homeowner’s radar. One way to get attention is to have an evangelist’s drive like Stanley Kolt of Active Ventilation Products in Newburgh, N.Y. The company started ventilating underground utilities in 1964 and introduced its first roof vent in 1977. After years of quietly promoting his products and philosophy about ventilation, he is surprised at the sudden attention he’s getting after being interviewed three times in the last two weeks. He likens the subject to a long-forgotten mistress who’s finally being courted.“Why doesn’t an attic deserve the same consideration (as roofing)?” he says. “A roof is a dynamic object. It should be treated with respect.”

Rather than getting as much circulation through the attic as possible, Kolt’s Pop Vent has a thermostat that reduces airflow 85 percent during the coldest months. He claims outside winter air is a big culprit in moisture migration to the roof, so the restricted circulation during the coldest months is sufficient to eliminate moisture that isn’t blocked by vapor retarders. The thermostat is calibrated to open the vent fully when the attic temperature reaches 90 degrees F. The product is sold to homebuilders and roofing contractors; it has also found a niche in manufactured homes.

“I believe in making everything simple ... If you’ve got controlled ventilation, you’re really taking in very little (moisture) and the roof can handle it,” he says. “Moisture is very clever. It follows the laws of God he set in nature. It chooses the path of least resistance.”

While the laws of man aren’t as permanent, Kolt’s views — backed up by university research — have contributed to a 26 percent increase in this year’s sales over 2002. He has seen mushrooms grow in Oregon attics and had to inspect some houses at night because the builder is fearful of lawsuits, so the final word on ventilation has yet to be spoken. Certainly there’s more science than faith in this debate, but it’s up to the roofing contractor to determine which “religion” he’s going to follow.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!